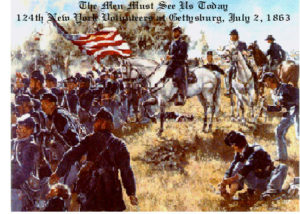

“THE MEN MUST SEE US TODAY”

Don Troiani Print

The 124th New York Volunteers at Houck’s Ridge,

Gettysburg, 1863

On the afternoon of July 2, 1863 a titanic struggle took place at Gettysburg between Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s First Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General James Longstreet, and elements of ultimately five Corps of the Federal army, led by Major General George Gordon Meade. The final defeat of General Longstreet’s attack was due as much to the skill and heroic sacrifice of tens of thousands of Federal soldiers as it was to any great feats of generalship on the part of the Federal officers. The 124th New York State Volunteers were one regiment that contributed to the defeat of the Confederate attack. Their story, and the story of the fighting that occurred at Devil’s Den on that hot afternoon, illustrates the fine fighting qualities of the Federal Army of the Potomac which were a primary cause of the ultimate Federal victory at Gettysburg.

Major General George Gordon Meade, commander of the Federal forces at Gettysburg, had hard choices to make on the evening of July 1, 1863, regarding the dispositions of his forces for the next day’s battle. He had present on the battlefield three of his seven corps, the I, XI and XII Corps. Yet of these three, two, the I and the XI, had been shattered by the first day’s fighting while the XII Corps was the smallest Corps in the Army, numbering little less than 9,000 men. Meade was expecting two other corps shortly, the II and the III Corps, while his remaining two corps, the V and the VI, should be up in the morning and afternoon of the next day. It seemed obvious to Meade, from information gained during that day’s fighting, that the Confederates were concentrated in front of him, while his own army was scattered and still coming onto the field. And the Confederates had the initiative, having driven the Federal troops from the field on the 1st of July.

Nevertheless, the Federal army was formed in an excellent defensive position. This position has come to be known as “the Fish Hook”, starting at Culp’s Hill on the Federal right, curving west and then south around Cemetery Hill in the center, and then continuing south to Little and Big Round Top on the southern part of the line, the Federal Left. Big Round Top was unsuitable for defense, due to its height and heavy tree cover, but Little Round Top was an excellent defensive position, and should serve to anchor the left of Meade’s line.

A natural bastion facing west and south, Little Round Top would be hard to take if manned by any decent amount of men. General Meade sent orders to Brigadier General Daniel Sickles, commanding the Federal III Corps, that when the Corps came up from the next morning, it was to take position with his left on Little Round Top and extending to the north along Cemetery Ridge, replacing units of the XII Corps which had occupied this position . Then General Meade forgot about his left flank, concentrating his energy on forming his available troops of the I, XI and XII Corps to defend the northern part of his line against the expected Confederate assault .

On the morning of July 2, Brigadier General Daniel Sickles, commander of the Federal III Corps, had major disagreements regarding General Meade’s dispositions of his forces. Fearing the rise in the ground in front of him would make an ideal artillery position, dominating the line drawn by General Meade along Cemetery Ridge, General Sickles sent message after message to Meade objecting to the position Sickles was ordered to occupy. Receiving no reply, Sickles took it upon himself to move his line forward, anchoring his left on a rocky, hilly area to the southwest of Little Round Top, known as Houck’s Ridge, and running generally northwest until it reached the Emmitsburg Pike, then North along the pike for about a half mile.

Houck’s Ridge runs generally northeast to northwest, facing southwest. The far left of Houck’s Ridge was known colloquially as Devil’s Den. The wisdom of General Sickle’s forward move is debated to this day. Its effect was to thin the Federal line so that was manned by only a single line of battle, without any depth and without any reserves. Whether a defensive line such as this could hold against determined enemy attack would depend to a very large extent on the mettle of the men holding it .

The 124th New York Volunteers was formed in August, 1862, in Orange County, New York. Enlisted for three years, or until the end of the war, the 124th had joined the Army of the Potomac in September, 1862, a few days too late to participate in the battle of Antietam. The 124th was present at the December 1862 battle of Fredericksburg, but did not participate in combat. The 124th’s first trial of combat occurred during the May 1863 battle of Chancellorsville where it, along with the rest of the Federal III Corps, helped fight off Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Corps for two days in some of the hardest fighting which occurred during the battle. By July 2, 1863 the 124th was considered to be a veteran regiment.

The 124th New York State Infantry, also known as the Orange Blossoms, was part of Brigadier General J. H. Hobart Ward’s 2nd Brigade, Major General David B. Birney’s 1st Division, III Corps, filed onto their position on Houck’s Ridge on the afternoon of July 2, hardly realizing the fight the New Yorkers would have to face. The march to Gettysburg had been hard, harder than anything they had made to date. In the past month they had trudged up from Virginia, sometimes doing twenty-five hot dusty miles a day in temperatures exceeding ninety degrees. The rigors of this life had taken its toll. Even in a veteran regiment such as the Orange Blossoms, the march had caused over ninety casualties, so that the regiment mustered only two hundred forty-five rifles on this hot afternoon. Their food was someplace miles away, the men were tired and hot. They had spent the morning fortifying a position near the hill to their rear (the now famous Little Round Top), which they had to abandon when forced to occupy the position on Houck’s Ridge.

Thus it is not hard to understand why the men spent the long hot afternoon resting, playing cards, joking and, especially, taking the ‘soldier’s prerogative’, sleep, instead of building breastworks as they should have been doing . This was one of the few breaks they had had in the whole horrid month, and they were enjoying it. And, it was early enough in the war that soldiers did not naturally build a safe position, as they would do without question later in the war. However understandable this break-down in discipline might have been, it was foolish from a military point of view, and potentially disastrous from the point of view of the Union army. That the enemy was close at hand should have been obvious; the sound of rifle fire to the west occasionally filtered through the trees, even with the air so heavily laden with moisture. Time spent on building breastworks might have saved lives, and certainly would have strengthened what was a naturally strong position.

The 124th New York was one of seven regiments composing Ward’s Brigade. The other regiments were the 3rd and 4th Maine, the 99th Pennsylvania, the 20th Indiana, the 86th New York, and two sharpshooter regiments (the 1st and 2nd United States Sharpshooters). All were veteran regiments. Some, such as the 86th New York, had served the entire war from the beginning. The 86th was a favorite of the men of the 124th, and the two regiments always sought to fight next to each other. The 86th was thus to the right of the 124th, with the 20th Indiana next to the 86th, and then the 99th Pennsylvania. The 3rd Maine had been detached to the skirmish line someplace to the West would not return this afternoon. The 4th Maine was to the left of the 124th, down in the valley below them and out of sight. The 4th Maine would be joined by other regiments later on, while the 99th Pennsylvania would be moved over to the 124th’s left, as the action started. But as far as Colonel A. Van Horne Ellis, the experienced commander of the 124th New York knew, his left was the left of the entire Federal line. He knew that his men had to hold the line. If his unit caved in, the whole Union line would fold up like an accordion.

The Confederate General James Longstreet’s First Corps had spent the whole afternoon moving into position to attack the Federal position on Houck’s Ridge. The original plan, designed by Robert E. Lee, called for an attack ‘en echelon’, which meant the attack was supposed to start on the far right of the Confederate line. As each regiment became engaged, the next regiment in line was to start its attack. The idea to force the Federals, to focus his attention on the original attacks, along the southern part of the line, leaving an opening further up the line. The attack was to start along the Emmitsburg Pike, southwest of Devil’s Den, and extend along the Emmitsburg Pike heading towards Cemetery Ridge.

General Sickles’ advance to a line bordering the Emmitsburg Pike changed the Confederate plan of operation dramatically. The Federals were not where they were supposed to be, and the change in Federal dispositions required improvisations in the Confederate battle plan. Furthermore, the march to the point of attack had not gone well. Mistakes had been made in the route chosen, causing the attacking force to change directions at one point, which required several more hours than originally intended to get the troops into their final attack positions. The attack thus began two or three hours later than it should have started. When it did begin, there was a big question as to whether or not there would be enough daylight for the attack to achieve its goal of breaking through the Federal lines along Cemetery Ridge.

In addition, the Confederate high command was not at all enthusiastic about this attack. General Longstreet opposed it from the beginning. Major General John Bell Hood, commanding one of General Longstreet’s key divisions, was convinced his men would be thrown away attacking the position he was ordered to attack. General Hood argued almost to the point of insubordination requesting a further time-delaying march around the back of the Federal position. It was obvious to many of the attacking troops themselves that it would be very difficult, if not impossible at all, to succeed in an attack like this. In most instances, over a mile of ground had to be covered, under Federal artillery fire all the way, before a single enemy soldier could be engaged.

To rear of the left of the 124th was Captain James E. Smith’s Battery, 4th New York Light Artillery, which had joined Ward’s position sometime around 2:30 pm. Smith brought six long-range Parrot rifles with him. These Parrot rifled cannons were excellent long-range guns, though when it came to short-range work they were not as good as other cannon would be under the same conditions. The position on top of Houck’s Ridge was too tight for all six guns. Two of the six guns had to be left down in the valley below Houck’s Ridge. To further add to the troubles of Captain Smith and his sweating artillerymen, the northern side of Houck’s Ridge was so steep that it was a struggle to get the guns up to their firing positions. Horses could not do it alone, and the men of the 124th New York had to pitch in to help. There was not enough room for the caissons, so the ammunition had to be brought up by hand from below (the rear of the hill).

Sometime near three in the afternoon, off to the south, some sort of activity in a line of trees caught the attention of the Union officers and men. Peering through their field glasses, the officers were able to make out several batteries of Confederate artillery rolling out from the woods. Clearly the folly of not having fortified this position must have crossed the mind of Colonel Ellis, as he peered across the open fields to the enemy artillery. Enemy infantry would surely be behind the artillery, ready to step out after the initial bombardment. But, it was too late to begin fortifying anything now. The boys were in for it. That much was obvious.

The Confederate guns opened up at 3:30 pm, and the bombardment was furious and accurate. Captain Smith’s battery replied in kind, sending shot after shot in the direction of the Confederate artillery. In fact, Captain Smith’s counterbattery fire was so intense the enemy was convinced they were opposed by more than one Federal battery! Smith was opposed by 12 Confederate guns. Colonel Ellis moved his men briefly into the nearby woods for protection against the iron storm. Soon, though, perhaps realizing that the flying wood splinters were hurting his men worse in the woods than if they were out in the open, Ellis moved them back into position along the ridge.

At 4:00 pm, from the woods in the distance, the Federal troops saw masses of Confederate troops moving out from the woods behind the Confederate guns. Though the Federals did not know this, these were some of the best troops in the Confederate army, Major General John Bell Hood’s division, containing, among other fine brigades, Brigadier General J. B. Robertson’s hard-bitten Texas brigade and Brigadier General Henry L. Benning’s Georgia Brigade. Over 10,000 Confederates were forming in double lines to face the awaiting Federal soldiers. The Confederates stepped out immediately on forming up, and reached the base of Houck’s Ridge around 4:30 pm. Their march there must have been a magnificent sight, flags flying every few feet up and down the line, four complete lines of battle perfectly ordered, officers riding back and forth maintaining order, their ranks continuously thinned by the accurate artillery fire of Smith’s Battery.

Reforming at the bottom of the hill, the Confederates started up Houck’s Ridge. When the Confederates reached within fifty feet of the Federal lines, Colonel Ellis let loose the combined firepower of the 124th New York, a volley which tore gaping holes in the Confederate lines. The Confederates recoiled, reformed, and came on again. Another volley from the Federals sent the Confederates scampering down the hill. Colonel Ellis’ men wanted to charge, and finally Ellis raised his sword. The New Yorkers charged their bayonets and, with a cheer, came pouring down the hill, alone and unsupported on either flank, after the dazed Confederates. The Confederates broke and ran from the raging Yankees, with the jubilant Federals racing after them. Few Federal troops could claim to have pushed back these tough Texan troops, veterans of some of the hardest fighting in the War. But the Texans had met their match this day in the Orange Blossoms, the 124th New York.

By the time the Orange Blossoms had gotten three fourths of the way down the ridge, a second line of Confederates was preparing to meet them. A mighty volley brought down many of the New Yorkers, including Major James Cromwell, Colonel Ellis’ second in command. The Orange Blossoms swelled forward to retrieve his body, forcing the Texans back again. A third line of Confederates leveled their rifles for a mighty volley, while other Confederates poured into a wall to the Federal left, firing on the regiment. Colonel Ellis rose in his saddle to urge his men on, the sword slipped from his hand, and his men saw him fall from his saddle. In the face of determined firing from the front and both flanks, the Orange Blossoms grudgingly made their way back up the hill, bringing the bodies of their two officers with them .

The Confederates then advanced slowly up the hill, firing from behind the wall at the bottom of the hill and from the many rocks which littered the field. The Federals could see the body of Captain Isaac Nichols, former commander of Company I, wedged between two rocks mid-way below the hill. Further down, at the farthest point of Federal advance, soldiers saw a hand waving through the smoke. This was Private James Scott of Company B, signaling encouragement to his friends on the hill above him. “When Cromwell dashed through the ranks to lead the charge,” says one of his comrades,

“Scotty was the first to spring forward after him, and when the Major fell it seemed to me Scotty changed to a wild beast. He had been wounded in the arm and his hand and face were covered with blood, but he did not seem to know anything about it, and kept on fighting until a ball hit him in the breast, and went clear through and came out of his back. That must have paralyzed him like, for his hands dropped and, as his gun struck the ground, he fell heavily forward upon it, as if he had been killed instantly.”

But Scott was not dead Though wounded twice more by shell fire, paralyzing all but his right arm, and once more by a bullet which broke two ribs Scott was still alive. He was captured and forced to endure the agonizing retreat of the Confederate army.

The 124th fought for another hour and a half , waiting for help. The bodies of their officers, Colonel Ellis and Major Cromwell lay on a rock behind them. At one point Private David Dewitt, arriving from the hospital just before Colonel Ellis died, said, “Boys, there’s Fifth Corps men down in back of us, but they are boiling their coffee before they come to our aid.” Whether this is true or not, (and it probably was not) the New Yorkers believed it, believing they had been abandoned. Every once in a while a man would drop a rifle which had become clogged or so hot that he could not hold it steadily. Bidding those beside him be careful where they fired, he would rush forward and pick up a weapon that had fallen from the hands of a dead or wounded comrade.

Meanwhile, the 99th Pennsylvania had been moved to the left of the 124th, intermingling with the 124th. The 86th New York and 20th Indiana were still on the right of the 124th. General Robertson’s Texans were moving from the Federal right, threatening to outflank the 20th Indiana and 86th New York. Meanwhile, on the Federal left, Benning’s Georgia Brigade had pushed back the 4th Maine below Devil’s Den. The 4th Maine took positions on the rocks of Devil’s Den, but the pressure was too much for them. Smith’s guns were now silent on top of the hill, their ammunition all gone and no men to be spared to drag the guns down the hill. The Confederates were pushing from all sides.

In the face of overwhelming numbers, and with their ammunition running out, the Confederates closing in to their front, left and right flank, and word that the V Corps was coming to relieve them, Ward’s Brigade was ordered to pull back. Smith’s guns were left to be captured. General Sickles had been severely wounded; General Ward, the former brigade commander, now commanded the division. The 124th was now commanded by Captain C.H. Weygant who, before the battle, had been fourth in line for command. The 124th withdrew down the hill and regrouped behind the Federal lines, losing more men on the way down Houck’s Ridge. No more than a dozen New Yorkers grouped around Captain Weygant near Little Round Top, as the regiment regrouped. Eighty one men gathered around the flag that night. More joined as the night went on, but ninety three would never rejoin the regiment again. Many of them were left behind on the field of battle, while many lay in a hospital, screaming in pain or silently waiting for the end.

The Confederates would eventually take Devil’s Den and Houck’s Ridge, holding it until the Confederate retreat on July 4. The Federal high command was able to rush enough extra troops to stop and finally push back the Confederate assault on Little Round Top, ending the fight for the left of the Federal line. It is highly doubtful, without the determined stand of Ward’s Brigade on Houck’s Ridge, whether the Federal line on Cemetery Ridge would have held. Little Round Top was the key, but the Confederate attack on Little Round Top was limited by the number of troops that could be brought to bear at the point of attack. Ward’s Brigade managed to engage the bulk of the Confederate troops attacking this portion of the field, troops which could have been used to attack, and probably overwhelm, the forces on Little Round Top. Without Ward’s lengthy defense of Houck’s Ridge, the Federal position could not have held. To quote a noted Gettysburg historian,

“…[this was] one of the most desperate encounters on the battlefield of Gettysburg, with close mortal combat between participants for that entire duration. The lengthy but almost bloodless delaying tactics of Brig. Gen. John Buford on the first day of the battle have gained historical significance on the story of the battle; the dramatic and drastic final assault by General Lee on 3 July is known by every school child. But neither of these heralded actions could possibly compare to the upcoming events at the southern end of Houck’s Ridge and in the Slaughter Pen. The tide of battle for Smith’s Battery changed so often and so rapidly that this action rivals that at the Wheatfield for not only drama and significance, but in confusion of eyewitness accounts and sequential narrative. Whereas at the Wheatfield troops from three Union corps were needed to hold back Anderson’s, Semmes’ and Kershaw’s Brigades, only Third Corps troops were used to hold this vital point against portions of Law and Robertson’s Brigades, and later Benning’s Georgia Brigade….if Sickles’ left fell before supports had arrived, it could have meant defeat for Meade’s Union Army.”

While the fight at Devil’s Den was not the finest moment for the 124th New York State Volunteers it certainly merits high praise. Some will argue that Catherine’s Furnace at Chancellorsville, or the Wilderness, or the Mule Shoe at Spotsylvania, or even Appomattox the true glory of the 124th New York volunteers shone. The 124th volunteers fought gallantly on every field of battle. At Devil’s Den, Gettysburg, the farmers and laborers who made up the 124th New York volunteers fought for two hours against overwhelming odds and did their job. They did no more or less than hundreds of other Federal regiments on the field of battle that day. They did their job and, by doing so, contributed to the great Federal victory that was Gettysburg.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1) Harrison, Kathy Georg, Our Principle Loss was in this Place, Action at the Slaughter Pen and at South end of Houck’s Ridge, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, 2 July, 1863, Gettysburg Magazine, Issue Number 1, July/1989

2) Pfanz, Harry, Gettysburg: The Second Day, The University of North Carolina Press, 1987 ISBN 0-8078-1749-x

3) Smith, James E. A Famous Battery and its Campaigns, 1861-’64, Washington: W.H. Lowdermilk and Co.

4) Tucker, A.W., Private, Company B, 124th NYSV, “Orange Blossom”: Services of the 124th New York at Gettysburg, National Tribune, January 21, 1886

5) Weygant, Charles H., History of the One Hundred and Twenty-Fourth Regiment, N.Y.S.V. Originally Published in 1877 by Journal Printing House, Newburgh, NY, Reprinted by Butternut Press, Baltimore, MD, 1986. ISBN 0-913419-45-1

6) Long, Roger, George J. Gross On Hallowed Ground, Gettysburg Magazine, Morningside House, Inc., 260 Oak Street, Dayton, OH 45410, January 1994, Issue